Winter is coming: England’s cricketers fly out for long tour that will decide Ashes and World Cup

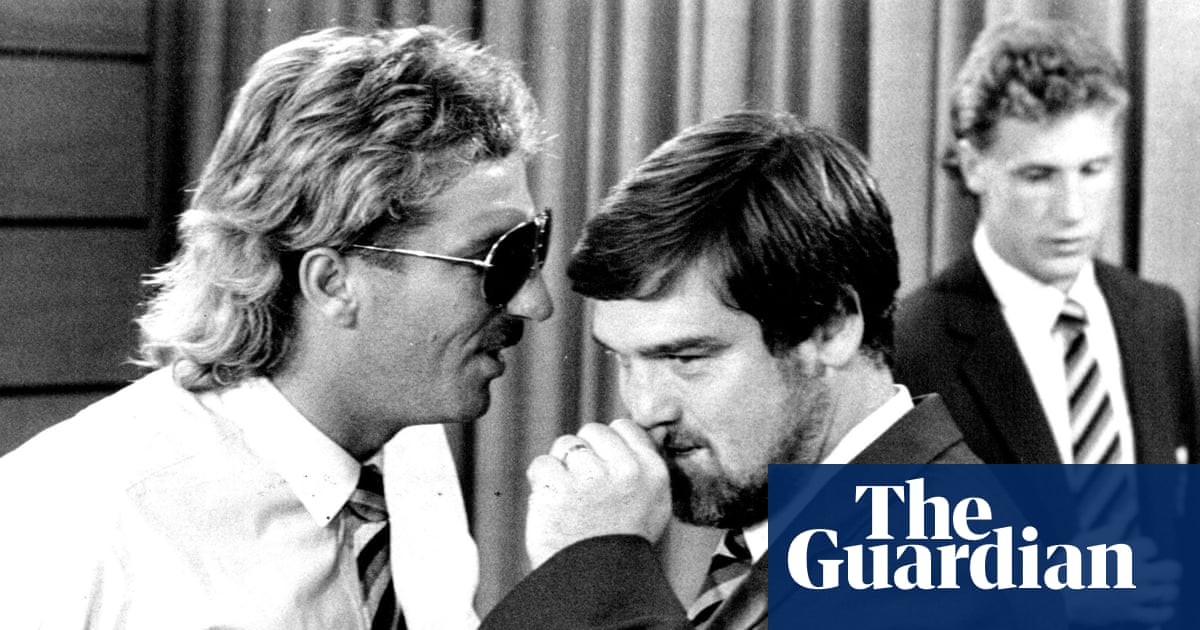

A meteorologist would say that England’s winter will start this year at midnight on 1 December; an astronomer would point a few weeks later to the 21st, perhaps even the moment at precisely 3.03pm when the northern hemisphere is tilted furthest away from the sun, the least sun-kissed moment of its least sunny day. But a cricket fan might go a little earlier, perhaps as soon as next Saturday at about 7.15am. Leaves might still be clinging to trees as yet unbothered by frost, but that is when the national side is scheduled to play its first fixture of a hectic touring schedule, and by the time it all ends the Ashes will have been decided, a World Cup will have been won, and it will be spring.For the players involved in all formats, these moments will bring a combination of excitement and perhaps also a bit of dread. The T20 squad departed for New Zealand on Friday, with the four men among them who have also been selected for the Ashes – Harry Brook, Jacob Bethell, Brydon Carse and Zak Crawley – knowing that only injury will bring them home within the next three months (and even then for no more than 10 days, before they depart again this time for Sri Lanka and from there a T20 World Cup in India).Four more members of the Ashes squad will follow along with the other ODI players not already there 10 days later, accompanied by a few Test bowlers, Mark Wood, Josh Tongue and Gus Atkinson among them, who are not due to play any white-ball cricket but want to work on their fitness. A full month before the Ashes starts in Perth most of England’s squad will be in New Zealand. There is only one official warmup game in Australia, against the Lions at Lilac Hill in the Perth suburbs, but by then few of the players should have any rust to work off.It is a formidable commitment, but not a novel one. Back in 1986 the players left one day earlier, on 9 October, and did not get home until 16 February. In the Guardian Matthew Engel raged that “the itinerary is an outrage … Lord’s have meekly agreed to a tour that treats the players as little more than air freight.” Graham Gooch, their best opener, took one look at the schedule and made his excuses. “My wife and I have just had twins, and my family commitments mean I can’t go away for four and a half months,” he said. “I studied the itinerary to see if I could get them out there but … I couldn’t make it work.”By the time the tour ended, Mike Gatting, England’s captain, was pleading with the authorities to learn and change. “We knew at the beginning it was going to be hard,” he said at the time. “We had an itinerary to fulfil and we’ve done it as best we can, but now the lads are tired.” When they landed at Heathrow, Gatting warned “too much cricket will kill a few players before they are ready to be killed”.Four decades later not a lot has changed, and if the state matches that used to pad out tours of Australia have been abandoned plenty T20s have sprung up to replace them. “That was a long, long trip,” Gatting says now. If today’s players don’t have it much easier, Gatting says those closest to them do. “It was the wives, looking after kids on their own, who struggled,” he says. “The families are looked after so much better than when we played. If they came out we had to pay for them, pay for their flights and their hotels, and quite rightly that’s all changed. Before it was horrible. There’s so much of a better atmosphere now. And there are probably only four or five players who will be involved in all of England’s games this winter, when we used to play all the competitions.”England played 30 games on that trip, including state and ceremonial matches, and Gatting appeared in all but four of them. Of the 19 full internationals across two formats and three competitions – the Ashes, the Perth Challenge (a four-team ODI tournament arranged to mark the America’s Cup and the completion of some new floodlights at the Waca) and the World Series Cup (another ODI tournament involving three of those same four teams), Gatting was one of six players who appeared in every one and eight who were picked at least 17 times. Miraculously, and against most expectations, England won the lot.“Playing for your country is what you aim for, always,” Gatting says. “It’s something you want to do. And in this day and age it’s made slightly easier because of the way families are treated and that’s so important. We struggled to make phone calls, we had to write letters home. It’s a hard trip, but going to Australia for the Ashes, it’s fantastic. As an England player it’s the one series you want to be involved in.”There are no repeats now of the experience of Worcestershire’s Don Kenyon, who returned from England’s tour of India in 1952 to meet for the first time a daughter who was already four months old. And compared with some past tours this is but a blink: when England boarded a train for Tilbury at London’s St Pancras on the morning of 18 September 1920 it started an unbroken period of 462 days – a little over one year and three months – in which either they or the Australians, who played in England the following summer, were on an Ashes tour. The English players were away for seven months and five days, Australia’s – having popped in to South Africa for three Tests on the way home – for nine months and two days. Compared with some of their forebears, it is not just with white balls and limited overs that Friday’s travellers are dealing in short formats.